ReCO₂gnition Trailer

Podcast Video

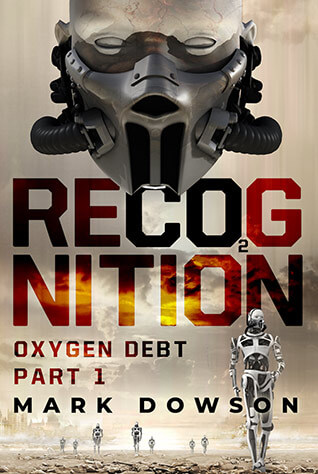

ReCO2gnition Book Review

Prologue

The early-morning sea was unusually calm as she swam gently, just breaking the surface with her glistening hair and shoulders. These moments were precious to her. When she was in the sea, nothing else mattered. She could clear her mind. She was confident in her body’s buoyancy and felt that the sea would always protect her. All was peaceful, almost timeless—until she heard the shrieks.

A small child leaped up and down on the water line, arms waving. The frantic cries were high-pitched and desperate. The shore was deserted; only the swimmer witnessed the chaos.

The warning cries stopped just as the sky darkened.

Chapter 1

Tightrope Walker

July 4, 2017

As the sun set over the Arno River, Dr. Ben Richards adjusted his lens. He zoomed in on the man creeping along a tightrope parallel with the Ponte Vecchio far below his terrace. As the man made his way freehand towards a platform about 120 metres away on the north side of the river, Richards hit the shutter on his sleek, black DSLR camera, set to continuous. Richards cast his mind back to an incident that occurred earlier that morning. Tragically, a delegate had collapsed and died right in front of him at a seminar he attended in Florence.

The man, thirty years Richards’ senior, had been sitting just three rows in front of him. Professor Towriss had devoted his career to the wind-farming industry. He was one of more than 200 people who had packed the main auditorium of the historic University of Florence’s Institute and Museum of the History of Science to hear the keynote speech of Professor Adam Robertson, head of the University of Glasgow’s Environmental Change and Society Research Programme.

Towriss had an apparent seizure shortly after Professor Robertson announced that all work in the field related to large-scale onshore and offshore wind farms was about to become obsolete, superseded by cheaper, more efficient methods of generation. Afterwards, some people seated near Towriss reported that the professor had looked distressed and was sweating heavily as Robertson undermined Towriss’ life’s work.

Robertson explained how most of the energy yield from large wind farms was lost from the point of generation to the end user. Much of Robertson’s argument was based on the unpredictability and inconsistency of blustery offshore winds, and the propensity of air masses in vast, open spaces to change direction and create wind shear and turbulence in the vicinity of turbines.

As he stared through his camera, Richards wondered about the inconsistency of the breezes issuing from the Arno and what might happen to the tightrope walker if he were to experience sudden and unexpected turbulence. But mostly Richards reflected on how cruel life could be, and on the utter unpredictability of fate.

Professor Towriss was a committed and respected member of the academic community, and in an instant his life’s work was obliterated, reducing him to an old man gasping for breath and fighting for his life. Sadly, it was a fight that he was destined to lose.

Richards was contemplating Towriss’ legacy in the field of sustainable energy generation when his train of thought was broken by a sudden change in the light as the sun disappeared behind a cloud and then re-emerged. As if distracted by the shifting light over the river, the man on the tightrope paused. Richards lowered the camera. He glanced to his right and saw tourists funnelling up the tree-lined avenue to the Piazzale Michelangelo above the river. Others were already standing on the square, pointing up at the tightrope. The upturned faces in the crowd glowed in the golden light bathing the piazza.

Richards lifted his camera again, training his eyes on the man, who had begun again his careful choreography. It was only then that Richards noticed what the funambulist was wearing. The man was dressed from head to foot in the livery of a court jester. He had a well-worn cap with what looked like ass ears protruding from each side. Beneath that, his motley was a patchwork of alternating gold and black squares. One of his tights was black, the other gold. On his shuffling feet the man wore black leather shoes curled up at the toes.

“It’s a panorama worthy of Titian, is it not?”

The voice startled Richards and came from a white-suited man with thick and unkempt black hair, raven eyebrows, an impressive moustache and a short beard.

“What’s it all about?” Richards asked.

“It’s a festival of what you English call folly. In our language buffoon means ‘a bag of wind.’ We love to make fun of the windbags.”

The man chuckled before drawing an MS cigarette from a white-and-gold packet with red and black letters. He offered one to Richards, who frowned and shook his head. As the end of the cigarette began to glow, Richards noticed words engraved on the side of the solid-gold lighter: SATOR AREPO TENET OPERA ROTAS

“Forgive me, but what does that mean?’

“It’s Latin,” the man said. “Its origin and translation are disputed.”

“But what do you think?” Richards asked.

The man was about to answer when there was a gasp from the crowd.

Richards turned back to the river below and looked through his viewfinder. The jester was now juggling four gold and blackballs.

“He is a brave man, I’ll give him that,” Richards murmured.

“Quite so,” the man on his left said, exhaling a white cloud.

Richards peered at the jester tiptoeing towards the orange terracotta rooftops just beyond the finishing platform. As he did, the shadows below thickened just as a thin shaft of light penetrated the clouds above, catching the jester in a moment of intense illumination. Richards hit the shutter button.

He was about to turn back to his new acquaintance when the crowd gasped again. He refocused his Olympus with a shaking hand.

“Oh no,” he cried.

A sudden gust of wind had blown across the river. The tightrope was now shaking like a washing line, and the jester, who no longer had a wide smile, tried desperately to regain his balance. He dropped all of his juggling balls, which fell haphazardly towards the meandering river below, and stretched his arms out like wings.

For a moment it looked like he would fall. But as suddenly as it had arrived, the wind died down, causing the wire to become tense again.

Richards sighed.

“He’s going to make it.”

But just as the jester started to take a few tentative steps, he froze. He opened his mouth in shock and clapped at his neck as if he’d been stung by a wasp. There were gasps. A woman cried aloud.

Then someone began to scream. The jester’s body seemed to atrophy as he fell clumsily onto the rope, which caught his fall before tipping him headfirst into the river below. Richards’ heart throbbed.

The crowds behind Richards pushed forward, desperate to see the cause of the clamour. Richards braced his back against the surge and lifted his head from the camera, gazing wide-eyed at the jester, whose limp and gaudy form was now about to submerge beneath the surface of the river. Richards leaned over the railings on the terrace and tried to raise his camera to make use of the zoom, but his arm was caught in the crush of the spectators.

“Here!”

The man in the white suit grabbed hold of his trapped left arm and forced it free. In a swift movement he raised the camera in front of Richards’ eyes and over his face.

“Thanks,” Richards muttered as he took the camera and hit the shutter release button.

“Prego,” the man replied.

Richards caught his breath again and gazed through the viewfinder. A white motorboat with a fluttering Italian flag had reached a point near the Ponte Vecchio, and several men in black wetsuits and fins tipped backwards into the river. A few moments later the sound of clapping began as the jester, now hatless, was brought coughing and spluttering to the side of the boat.

The relieved onlookers on the piazza lit cigarettes and dispersed towards the restaurant behind. Richards was about to turn when something caught his eye through the viewfinder; he noticed a scratch on the lens. Richards rubbed his eyes and then wiped the zoom lens with a handkerchief. He swivelled it back and looked through the electronic eyepiece. It was still there.

“Damn!” he cried.

He looked left, but the bearded man had gone.

Richards reached for his camera bag on the ground and retrieved the cover for the zoom lens. As he knelt to screw it on, he saw something near his left shoe. Next to the smouldering butt of an MS cigarette was what looked like a red-winged dry fly, the kind a fisherman would use to lure trout—only it wasn’t a fly. It was a tiny dart from a high-powered rifle.